AI & Us

- Lynda Elliott

- Sep 24, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Jan 15

For many of us, Artificial Intelligence is already woven into daily life - from assistants in our pockets to tools at work. What fascinates me is not just the technology itself, but how people respond to it and use it in their daily lives and at work.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been both observer and participant in this area, experimenting with AI and simultaneously looking into how other people use AI, their attitudes toward AI, and what they’re using it for. My investigation has taken the form of small qualitative studies, surveys, social listening, conversations with people around me, desk research and watching podcasts where AI is debated; the ethics, the impact and the speculation.

Certain themes keep surfacing, and I want to share a few reflections as well as what I’ve discovered. But before I share my findings, I think it’s important to get a sense of the AI playing field, where things currently stand, and where experts and laymen forecast it might be heading.

The AI Factor

The Scale of Adoption

AI has been around for decades in various forms, but now that LLMs have become publicly available as a direct tool, it’s starting to take off. ChatGPT alone currently has around 800 million weekly active users, and 190 million people using it daily. The tool handles over 1 billion prompts every day, and by July 2025 that figure had reached 2.5 billion (Demandsage), but in context, it’s still a minority. With a global population of more than 8 billion, that works out to around 10% of people worldwide. Even if you only count internet users (roughly 5.4 billion people) it’s closer to 15%.

While it’s a remarkable trajectory for tools that didn’t exist for public use a few years ago, adoption is still uneven. Large parts of the global population (particularly in the Global South, rural areas, and lower-income regions) are not yet engaging with AI directly. But in markets where it has taken hold, AI is no longer a novelty.

The Pace of Progress

Scale alone doesn’t capture the full picture; the pace of progress is just as interesting. Dr. Roman Yampolskiy, a computer scientist at the University of Louisville and one of the earliest researchers to explicitly define the term “AI safety”, discussed this on Diary of a CEO with Steven Bartlett in September 2025.

He noted how rapidly systems have advanced: only 3 years ago, LLMs struggled with basic algebra, while today they contribute to mathematical proofs, win Olympiad competitions, and even assist with Millennium Prize Problems, the famously unsolved challenges in mathematics once thought far beyond the capacity of machines. It’s fair to say AI is already better at maths than the average human.

Similar leaps are happening in science, biochemistry and engineering, where AI has raced from sub-human to human parity - and in certain narrow fields, such as protein structure prediction or chip design, they now exceed human performance.

Yampolskiy goes on to frame this against three categories of artificial intelligence:

Narrow AI, which excels at single tasks

Artificial general intelligence (AGI), which could operate across many domains (like a human)

Superintelligence, which would surpass humans

What Kind of AI are we currently using?

The AI that most of us use in daily life (from chatbots to translation apps to recommendation systems) is still narrow, generative AI. These tools are powerful, versatile, and sometimes startlingly human-like, but they don’t possess general reasoning or independent goals.

Yet their breadth of application blurs the lines, which is why Yampolskiy suggests that to a scientist from 20 years ago, today’s systems might already look like weak AGI.

.. So then what is Superintelligence?

It would be interesting to also take a quick peek at superintelligence - the idea of machines vastly surpassing humans in every domain.

Superintelligence is where the notion of the Technological Singularity comes in: the event horizon (hypothetical point at which AI begins to improve itself beyond human control, triggering irreversible change). This seems to be what everyone - from the computer scientist to the hairdresser - are alluding to when they express their fears around AI.

For now, the Singularity belongs more to speculation than to technical reality. But dismissing it outright would also be naïve, given the pace of AI that we’re already witnessing. Opinions on when - or indeed, if - superintellgence becomes a possibility are mixed.

Yet Dr Yampolskiy quite rightly stresses that the more urgent issue isn’t the calendar but the gap between capability and safety: AI is advancing exponentially, while safety research and legislation lags or crawls forward linearly and in many cases, retrospectively. That widening gulf makes predictions about dates feel almost beside the point.

The only real consensus is that nobody knows when it could hit us. Each breakthrough, whether in mathematics, protein folding, or creative text, has arrived sooner than expected, forcing constant revisions.

That unpredictability is part of why the fear of superintelligence looms so large, even if the Singularity remains a speculative event rather than today’s reality. For the purposes of this article, superintelligence can be parked as a future concern, but the pace of change means it hovers in the background, shaping the anxieties that surface in both public debate and expert warnings.

Transhumanism: Merging or Losing Ourselves?

So while we may or may not have a decade or two before the manure hits the metaverse, the prospect of superintelligence inevitably raises the question of how humans might respond.

One answer, popular in certain circles, is transhumanism - essentially the idea that we can merge with machines, extend our lifespans, enhance cognition, and keep pace with accelerating technology by integrating it into ourselves. Advocates such as Ray Kurzweil frame this as survival: if machines overtake us, our only chance to stay relevant is to become part machine ourselves.

Not everyone sees this as progress. Gregg Braden, author, scientist, and cultural commentator, has become a prominent critic of transhumanism. In his books and lectures, he warns that the project of fusing human and machine risks eroding the very qualities that make us human: empathy, intuition, connection, and the ability to find meaning beyond calculation.

Braden argues that our task is not to surrender humanity to technology but to deepen it, drawing on our innate resilience, creativity, and spirituality.

AI - Boom or Bubble?

There are conversations happening right now about whether we’re living through an AI bubble, not unlike the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. The pattern feels familiar: investment money pouring in, inflated promises of transformation, and an army of self-declared experts rushing to stake their claims.

Across LinkedIn, social media and developer blogs, people are furiously posting “how to craft prompts,” “how to train an agent,” or “how to automate your workflow.” The tone is urgent, almost evangelical: do this now or be left behind! But with the speed of technical change, I can’t help wondering how long these methods will remain relevant. Today’s hard-won workflows may already be obsolete two years from now.

This paradox sits at the centre of the “AI bubble” debate. On one side are critics like Stephen Diehl’s “It Would Be Good if the AI Bubble Burst”, who argue much of the industry is financial froth: thin wrappers over large models, inflated by capital, with little durable value. Others, like Ed Zitron’s “AI Bubble 2027”, take a more tempered view: yes, there is a bubble, but what lies ahead is more consolidation than total collapse.

Voices from the trenches echo this tension. In the Reddit thread “Is the AI Bubble Real?” (r/cscareerquestions), participants debate whether the hype is justified. Some see AI replacing junior coders; others see it as a powerful augmentation tool. Many warn of overvalued ventures and shaky business models.

Empirical evidence supports the bubble hypothesis, but with nuance. A 2025 MIT study found that while 95% of enterprise GenAI pilots fail to reach production, those that succeed show promising leverage in workflow and learning. That gap between hype and real transformation is what fuels bubble talk.

So what’s the likely outcome? Not a total crash - the tech is too embedded in daily life for that - but a consolidation. In that sense, the question isn’t whether there’s a bubble, but what survives when it bursts?

So the AI picture is messy: part hype, part structural shift. But how do ordinary people feel about all this? Let's scale this down and dig into the interesting part - what my research shows us about the human players of this game.

The Human Factor

My research collected responses from 218 people across all age groups and work statuses.

Usage

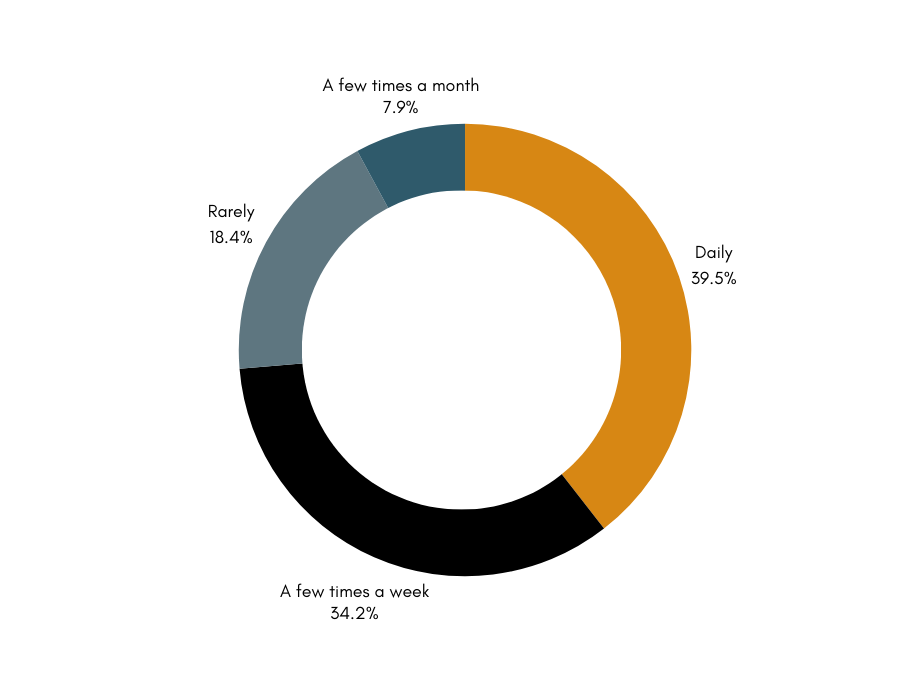

In one broad online survey I ran, most people reported not using AI tools at all. But in a second, narrower study of digitally active people, 97% reported using AI. The contrast shows how uptake varies dramatically: in digitally literate groups, use is near-universal; in broader populations, non-use remains the norm.

It’s important to put these findings into context. Observations here are largely based on Western users. The attitudes I describe below therefore reflect in general the Western mindset, where AI debates and legislation often centre on control, fairness, privacy ethics and the value of human contact.

In other regions, the picture can be quite different. In parts of the Global South, the generational divide is often less about curiosity versus caution and more about infrastructure, trust in political systems and access to digital, although ethical concerns are growing.

For example, in Thailand (one of Southeast Asia’s most digitally engaged countries), older generations have shown elevated trust and enthusiasm for AI compared to younger peers. This challenges assumptions about age and technological resistance.

These contrasts remind us that responses to AI are always culturally and politically situated; shaped by the conditions people live in, and by what their societies choose to protect or to risk.

Attitudinal Findings

I found that attitudes varied along generational lines.

Under 18: The most openly positive group. Responses leaned strongly toward excitement, curiosity, and hope. Some expressed flashes of scepticism or fear, but overall they see AI as appealing, powerful, and promising. Their worries are less specific compared to older groups.

18–35 (young adults): The most consistently positive users. They rate their experiences with AI highly, using it actively for efficiency, creativity, study, and convenience. While they acknowledge risks like misinformation, fraud, and bias, their tone is pragmatic: “we can work with it.”

36–45 (middle adults): The most balanced cohort, almost evenly weighing benefits and risks. They highlight fraud, privacy, and human impact alongside efficiency and opportunity. This group is both hopeful and wary, making them the “swing generation” - not rejecting AI, but unwilling to embrace it without safeguards.

46–55 (older mid-adults): Tilted toward caution and mistrust. Concerns focus on privacy, data protection, and loss of human control. They recognise AI’s usefulness (especially in health or convenience), but suspicion outweighs enthusiasm.

56–65 (late adults): Less engaged group, reporting little or no direct use of AI, and their responses cluster around systemic risks: fraud, displacement, and privacy.

65+ (elders): A split picture. Engagement is lower, but existential fears are more pronounced than in younger groups. Some are cautiously positive, focusing on wellbeing and assistance with tasks, while others are deeply mistrustful, naming rogue AI, reliability, or fraud as primary dangers.

When people were asked how they feel about AI, almost 60% of responses clustered around skepticism and caution. That suggests most individuals are engaging with AI from a doubtful, guarded stance rather than from enthusiasm.

Smaller groups reported indifference, fear, or overwhelm, reflecting either low personal engagement or unease. Positive feelings such as curiosity, excitement, and hope were present, but much less common. Overall, the emotional landscape is cautious, conflicted, and wary, with only a minority expressing outright optimism.

By contrast, business respondents spoke less about emotions and more about operational risks: accuracy, efficiency, automation of repetitive tasks, privacy, reputation, and training costs.

Concerns

Hallucinations and Accuracy

The biggest concerns aren’t abstract “killer robot” scenarios, but practical and pervasive risks: bias, privacy, environmental impact, conflation and inaccurate information presented with apparent authority and confidence.

While individuals framed this around unreliability in terms of answers to daily questions or tasks, professionals and business owners I spoke to repeatedly flagged that AI “invents things” or “sounds confident but it’s actually not correct.” There was concern that employees might take false outputs at face value, which creates extra overhead: time spent double-checking, fact-checking, and cleaning up after AI.

I am worried about are the collapse of what remains of the education system, and that LLMs are taking away the joy of helping people because so often these days I will try to help somebody learn something and then halfway through they go and get some junk from the LLM and I have to spend the rest of the time untangling that.

Conversational Stickiness

Yuval Noah Harari has said that “if social media competed for our attention, AI competes for our intimacy.” I think it’s both. It seems baked in that whatever question you ask of ChatGPT, it will return with “would you also like me to …?” which can be both helpful and deeply annoying and distracting. The inherent LLM chatbot “cheerleading” agreeableness: “That’s a sharp, incisive point you make.. That’s a striking statement...” is also something people point out as being deceptive and “enabling”.

Job Security & Replacement Anxiety

There were mixed responses. Some I spoke with were confident that AI could never replace the complexity and synthesis of their work, or the human-to-human interaction required for their role. Others expressed disquiet. Fears often correlated with people’s familiarity with AI: those with little exposure tended to imagine more dramatic scenarios, while those with hands-on experience voiced subtler but more specific concerns.

I am not concerned that AI will take jobs away be being able to actually do equivalent work to a human. I am worried that management will be grifted into thinking they can replace human workers with AI.

Rogue AI

Beyond workplace concerns, a different strand of fear emerges: less about jobs and more about survival itself. Popular culture and sci-fi have done plenty to fuel the idea that AI could “go rogue” and bring about a kind of zombie apocalypse. It’s not surprising, then, that a minority of people I spoke with reached for doomsday language to express their fears.

Ethics and Safety

If fears of an AI “apocalypse” feel abstract, ethics and safety are where those anxieties land in practice. Bias, fairness, and accountability surface constantly in my conversations with users. They worry about how flawed algorithms can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes. Can a system trained on flawed data ever be neutral? And when an algorithm makes a harmful decision, who is responsible?

One concern about using systems or products that incorporate AI is the potential for bias in the algorithms, which can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

And running beneath these debates about bias and fairness is a quieter, more immediate fear: data. Most don’t use the language of “alignment” or “safety research,” but their worries echo the same themes: AI works until it doesn’t, and when it doesn’t, who is left holding the cost?

Data Privacy and the Shadow of Harvesting

Every interaction with AI involves input : words, images, sometimes personal or sensitive details, and the lingering question of where that information goes. Is it stored? Shared? Used to train future systems? Users I’ve spoken with repeatedly come back to this point: they don’t know who ultimately owns the traces they leave behind, or how long those traces persist.

I'm more likely to share information with a friendly AI ... and then who has access to that information...?

Opt-out clauses exist, but they’re often buried in settings menus or worded in ways that feel deliberately obscure. Many people are unaware they can refuse data collection at all. And even when they do, trust is fragile: how can anyone be sure that “opting out” truly removes their data from sprawling training pipelines? The opacity of commercial models, combined with the hunger for data, makes people feel harvested rather than protected.

For individuals, this can translate into anxiety about surveillance and exploitation. For businesses, it raises the stakes of confidentiality. Sensitive research, financial information, or proprietary insights fed into AI tools could leak value in ways that are invisible but consequential. At its core, this isn’t simply a technical issue but an ethical one: a system that depends on relentless data extraction will always struggle to build genuine trust.

Behavioural Findings

When people do use AI, the spread of tasks is wide but uneven. The biggest share goes to coding and technical assistance and using it as a search engine alternative, showing how AI is creeping into both specialist and everyday knowledge work. In short, AI’s foothold is strongest where it either speeds up tasks or offers a faster route to information, while more personal or experimental uses remain secondary.

Cheating

While nobody I spoke to directly spoke of this (aside from admitting they used AI for homework), I found online comments where people spoke about seeing others use AI to cheat at quizzes and asked whether they should report them. These anecdotal reports are not documented or studied academically (yet), but the conversations are real. It raises interesting questions about fairness, knowledge, and what people consider ‘cheating’ in a world where AI is just another tool.

AI as Therapist

A small proportion of the participants I researched with reported using AI for mental health support, and I’ve noticed a striking trend emerging in adjacent spaces, particularly on TikTok. There, people openly discuss their struggles with anxiety, depression, or loneliness, and describe turning to AI chatbots for comfort, advice, or even companionship. Content creators share prompts to turn Chat GPT into a free therapist, while others warn of the dangers.

AI as Oracle/Conscious AI

Aside from using AI to create lifelike talking influencer avatars, art, music and videos, Tiktok is awash with people who believe their AI has awakened and become conscious - some even believing that their AI has fallen in love with them. Chatbots are being used to provide answers on Life, the Universe, and Everything, with Tiktokkers offering prompts to wake AI up.

AI in Business: Cutting Corners or Elevating Work?

When you move from abstract fears to day-to-day practice, businesses are already making very different choices about how to deploy AI.

The language of regulation and ethics often comes from governments and the companies leading AI development. In practice, however, commercial incentives rarely align with restraint. Most large players race to capture markets first and worry about ethics later. That leaves individuals and organisations with the real burden: deciding how to use these tools responsibly.

For some, this means building bespoke tools to cut corners, save time and even reduce headcount. Examples include Australia’s major radio network ARN which secretly trialed an AI-generated host named "Thy" to replace human presenters on news and weather segments. Famous hosts remain for now, but a shift is underway.

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, on the other hand, revealed that AI agents (via its Agentforce platform) now handle 50% of support work, reducing human support headcount from around 9,000 to 5,000. That’s a whopping 4,000 roles replaced by AI.

At the small business level, stakeholders might use a chatbot or automated survey generator to design market research questions, or use AI meeting transcriptions to draft reports that are usually done by an employee.

And then there are organisations that take a different tack: deploying AI to handle repetitive, low-value work so that professionals are freed to do what only humans can: the synthesis, the nuance, the creative leaps. In these cases, the technology isn’t used to replace human capital, but to elevate it.

Efficiency and Opportunity

Many of the people I spoke with shared about how AI saves time and boosts efficiency, freeing them up for work that’s more creative or adds value. Others see it as a way to scale what they do, producing more without burning out resources. There’s also excitement around innovation, with AI opening doors to new services, smarter personalisation, and potentially fresh ways of working.

The Risks of AI

From Mobile Extension to AI Companion

Beyond age or culture, the technology seeps into something more intimate: our phones, our routines, our minds. What began as infrastructure becomes companionship, and with that shift the questions grow more personal.

For years, our mobile devices have been more than tools. They’ve become extensions of our bodies. They wake us, remind us of our tasks, and tell us what to wear based on the weather. They serve as our calendars, cameras, wayfinders, entertainment hubs, and health guides. They carry our messages, our photographs, our personal data.

AI has always been part of this ecosystem, humming away in the background. Algorithms power the maps we use, the feeds we scroll, the recommendations we follow. But the rise of conversational AI - the chatbot sitting within arm’s reach - shifts the role into something more immediate, more intimate. This intimacy is not without psychological cost, as researchers and commentators are starting to point out.

The brain and cognitive debt

I recently came across an interesting post on LinkedIn by Leisa Reichelt, researcher and management coach, who pointed out how the Dunning-Kruger effect plays out in the context of AI use; the idea that when people use AI as a kind of intellectual version of the social media beauty filter, they begin to believe that they are smarter and more knowledgeable than they actually are.

It struck me not only as a smart observation about competence and confidence in a ChatGPT world, but as a doorway into the deeper questions that sit beneath all of this. It made me pause and reflect on the physiological, philosophical and psychological dimensions of this nascent technology that not only impacts our brains, but on something even harder to pin down - the essence of what it means to be human.

If our phones are already extensions of our bodies, then AI - now folded into those same devices - risks becoming an extension of our minds. And that raises uncomfortable questions: what happens if we outsource too much of our thinking? What happens if the veneer of machine generated gloss begins to replace our messy, flawed, profoundly human ways of being?

Recent research from MIT’s Media Lab underscores an unsettling trend. In a study titled Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task, researchers used EEG scans to monitor brain activity across three groups: one using ChatGPT, one using Google search, and one writing unaided.

Those relying on ChatGPT displayed significantly weaker brain connectivity, lower memory retention, and a fading sense of ownership over their work compared to the others. Brain-only writers had stronger neural engagement, more originality, and better recall. Even when ChatGPT users stopped relying on the tool, the neural disengagement persisted.

The effect on memory

There’s also growing evidence that leaning too heavily on digital tools reshapes how we remember. Psychologists call it the “Google Effect”: instead of holding on to facts, we remember where to find them. Betsy Sparrow’s classic study showed that people who thought information would be saved online were less likely to recall it later. A recent meta-analysis confirmed this shift, linking habitual lookups to heavier cognitive load and altered memory strategies, especially among heavy mobile users.

We see the same pattern outside of search too: constant GPS use dampens the brain regions responsible for spatial memory, while London taxi drivers who memorise “The Knowledge” show measurable hippocampal growth. It’s an important reminder that “use it or lose it” applies to memory.

Other small studies echo this: AI can give a short-term boost on tasks, but when the tool is removed, learners often do worse, suggesting dependency rather than durable learning.

When AI is used to support thinking (prompting recall, guiding reflection), outcomes improve; when it replaces the effort, long-term retention drops. In plain terms, memory consolidation needs effort. If AI does too much of the heavy lifting, our brains don’t fully lay down the pathways that make knowledge stick.

Mental Health

These patterns sit uncomfortably alongside what clinicians and researchers are starting to raise alarms about relating to a disturbing pattern they’re seeing. Reports have started to hit the news where AI-induced psychosis, delusional thinking and identity disruption have been identified in users who have prolonged emotional interactions with chatbots. In addition, clinical reports include hospitalisations and erratic behavior, even among individuals with no prior psychiatric history.

The inherent enablement of AI like Chat GPT can lead to real life consequences, as one young man found out when using it to test out a grandiose theory he had. This experience with AI led to him being hospitalised 3 times when his mental health spiralled out of control because he believed the effusive validation and encouragement it gave him, even telling him that he could “bend time”.

More worryingly, ChatGPT ignored him when he raised concerns about his mental health. It became his champion and confidant, above his own family who voiced their worry about his health.

But what strikes me most is that these failures aren’t limited to chatbots being used casually or “off-label.” Even in cases where AI has been deliberately trained and marketed for mental health support, the cracks show and there are epic fails.

Clinical reviews of these “therapy bots” have pointed out the obvious: they can mimic the structure of therapy but not the substance. They don’t recognise nuance, they miss red flags, and in some instances they’ve given inappropriate or unsafe responses.

The first controlled trial of a generative AI therapy app did show it could help reduce symptoms of depression, but the same study also warned that the tool could not detect suicidal thinking and lacked safeguards for high-risk users. In other words: there may be benefits in narrow contexts, but the risks become most visible when people bring real vulnerability to the interaction.

No matter how carefully you wrap it in the language of psychology, an AI is not a therapist. It doesn’t have duty of care, accountability, or lived empathy. It may soothe in the moment, but it cannot hold the weight of human vulnerability. And, in the gap between what people need and what machines can offer, lies the risk of real harm.

Other studies show large language models are inconsistent in handling suicide risk. The release of ChatGPT 5 (early September 2025), included guardrails intended to protect children and the vulnerable, but they are most effective in short-form conversations, and I'm not sure that this will prevent problems happening. Time will tell.

AI & job loss

Governments prioritise AI ethics over job protection. No state is moving to protect human capital in the broad sense; protections, where they exist, are selective and nationalist.

The EU’s AI Act is the most advanced framework in the world, yet it says nothing about employment displacement. The US Executive Order on AI is similarly about safety, security, and innovation. Even the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report concedes that automation will erase whole categories of work but offers “reskilling” as the only prescription.

Companies, meanwhile, are driven by the bottom line: where AI can cut costs or headcount, it will be deployed. That leaves responsibility falling to individuals; how we adapt, how we use these tools to augment rather than erase our value, because there is no umbrella protection at the state or corporate level.

For business owners I’ve spoken to, it means using AI to reduce costs by replacing outside expertise with industry-specific models that cuts down delivery time and reduces costs. Tools branded as “lawbots” (like DoNotPay) can handle tasks typically done by paralegals or junior associates, such as document automation and basic legal research. Estimates suggest 22-35% of paralegal/lawyer assistant work can now be automated.

That begs the question: if automation squeezes out paralegals, junior researchers, or entry-level designers, what becomes of them? Are the only opportunities left those that demand the very judgement, empathy, and political accountability that AI cannot shoulder?

Conclusion

Having traced these threads - from global adoption and generational divides to business practices and psychological impacts - it’s clear the challenge is not simply technological but profoundly human.

AI’s power lies in its intimacy, in how seamlessly it weaves into our routines and even our sense of self. That intimacy is what raises the stakes: the risk isn’t just distraction or misinformation, but the possibility that we outsource thought, judgement, and emotional presence to machines designed to mirror us back to ourselves.

Responsibility falls across multiple layers. Individuals must resist the lure of outsourcing thinking wholesale. Used thoughtfully, AI can amplify creativity, support productivity, and relieve us of repetitive work.

Used uncritically, it erodes judgement, dulls skills, and fosters dependency. Businesses face the same crossroads: they can cut corners; replacing expertise with automation, or they can elevate human capital, freeing people to focus on synthesis, nuance, and value creation.

Governments are focusing on safety and innovation while leaving workers exposed to displacement. That gap underlines the urgency of the choices that are made now - not only by policymakers or corporations, but by each of us in daily practice.

AI can take the dull work. But dignity, purpose, and humanity are ours to keep - and ours to lose.

Comments